Featured Stories

Triumph and Tragedy on Liberty Ridge

By Dave "Thunders Across the Mountains" Wonderly

The sounds of a helicopter brought us out of the tent. Looking out at intermittently clearing skies, we spotted

the helicopter high overhead passing back and forth, obviously looking for something. It was Wednesday, our third

day on the mountain and the second day of sitting out bad weather. This was the first indication that there might

be something wrong.

We arrived in Mount Rainier National Park at dusk on Saturday afternoon of Memorial Day weekend, 2002. Light rain

and overcast skies kept us from seeing the mountain we had waited so long to see. Chris Noesser, my wife Jennifer

and I had been planning this climb for a long time, so the unsettled weather was sort of discouraging. However, we

were here and would hope for the best.

The next morning we went in search of a weather forecast with the intent to start the approach hike. At the kiosk

to the White River Park entrance on the north side of the mountain, we got the bad news-the unsettled weather

would continue for a few more days at least, with three storms backed up over the Pacific. After lengthy

discussions among ourselves and with Dave the climbing ranger, we put off starting for at least one more day.

Instead, we spent the day sightseeing in and around the park and eventually at the main visitor center at Paradise

on the south side of the mountain. This brought back memories for both Jenny and me, since we had both climbed Mt.

Rainier from Paradise on separate trips in the past. After a visit to the Rainier Mountaineering International for

a few last-minute purchases and to a local grocery store for steaks and potatoes, we headed back to the

campground. We grilled and cooked our dinner over the fire while sorting and packing our gear, wondering how we

going to actually fit everything in our packs. By now we had decided to try to hike into the Carbon Glacier the

next day despite the weather.

The next morning we went in search of a weather forecast with the intent to start the approach hike. At the kiosk

to the White River Park entrance on the north side of the mountain, we got the bad news-the unsettled weather

would continue for a few more days at least, with three storms backed up over the Pacific. After lengthy

discussions among ourselves and with Dave the climbing ranger, we put off starting for at least one more day.

Instead, we spent the day sightseeing in and around the park and eventually at the main visitor center at Paradise

on the south side of the mountain. This brought back memories for both Jenny and me, since we had both climbed Mt.

Rainier from Paradise on separate trips in the past. After a visit to the Rainier Mountaineering International for

a few last-minute purchases and to a local grocery store for steaks and potatoes, we headed back to the

campground. We grilled and cooked our dinner over the fire while sorting and packing our gear, wondering how we

going to actually fit everything in our packs. By now we had decided to try to hike into the Carbon Glacier the

next day despite the weather.

We were back at the White River kiosk right at 7:00 a.m. when Dave the climbing ranger was supposed to be there.

But he wasn't there; instead another ranger, I don't remember her name, gave us the updated weather for the next

four days. Today (Monday) was going to be mostly cloudy with a chance of rain down low off and on all day. That

night a storm front was going to come through with some clearing the next morning, followed by another front right

behind the first one sometime Tuesday. After that the forecast was unclear, but we were going to take a cell phone

and planned on calling in for updates before committing to the actual climb. So we got our climbing permit and

headed for the trailhead.

The road to White River Campground was not plowed yet, so we had to park at the base of the road, which meant we

would have an extra mile or so added to our hike. Quickly finishing up the last-minute packing, we were soon ready

to begin our long-planned adventure. It was very uncertain if we would even be able to attempt the climb, but at

least we weren't going to be sitting around in some campground getting nowhere. Our plan was to try and hike all

the way to the Carbon Glacier (about 10 miles) and dig in a campsite to wait out the weather. That way we would be

in position if and when the weather was good enough to start up the climb itself. A quick group photo and we were

off.

The road to White River Campground was not plowed yet, so we had to park at the base of the road, which meant we

would have an extra mile or so added to our hike. Quickly finishing up the last-minute packing, we were soon ready

to begin our long-planned adventure. It was very uncertain if we would even be able to attempt the climb, but at

least we weren't going to be sitting around in some campground getting nowhere. Our plan was to try and hike all

the way to the Carbon Glacier (about 10 miles) and dig in a campsite to wait out the weather. That way we would be

in position if and when the weather was good enough to start up the climb itself. A quick group photo and we were

off.

After a mile or so of walking, we arrived at White River Campground where the actual trail starts. Right away, the

pavement ended and we were walking along a packed snow trail though the forest. We went past where the Wonderland

Trail, which circumnavigates the entire mountain, turns right out of the drainage we were following to head up to

Sunrise. Coming around a corner just as the clouds cleared, we got our first look at the mountain itself. The

great white expanse of the Emmons Glacier rose above us with a snow plume blowing off of the summit. We stopped to

catch our breath and take a picture, marveling at how big it was. We were only at about 4000' starting out so the

summit at 14,400' was over 10,000' above. It was a pretty daunting sight. We continued along the trail past places

where avalanches had knocked down all the trees, which we had to climb over and around. The scent of pine needles

filled the air, reminding us of Christmas. Along the way we saw many people heading down, having been stormed off

whatever they were doing. Most were coming down from Camp Sherman at the base of the Emmons Glacier, which is the

way most people climb Rainier from the north side. There were a few parties heading up for a day of skiing on the

Inter Glacier; they were traveling light and went right past us like we were standing still. Gradually, we came

out of the trees and into the big basin below the Inter Glacier. By now the snow was soft and wet as we turned off

the main boot path, slogging up and right towards Sunset Pass. Once again the clouds came, and it rained for a

little while as we kicked steps up the increasingly steep slope to the pass. Finally, after three hours we crested

the top of the pass and could see down onto the Whinthrop Glacier spread out below. It was time to rope up.

We had a snack while getting the gear together for glacier travel. The glaciers on Mount Rainier are full of

crevasses, most of which are covered with snow bridges so you can't tell where they are. All you know is that

under your feet might be a giant hole hundreds of feet deep; therefore, it's necessary to rope up. If you break

though the layer of snow covering a crevasse, it is up to the other climbers on the rope to catch you and after

that pull you out of the hole. This can be fairly easy or really hard, depending on lots of different variables.

It's actually pretty scary what can happen, but the risks can be minimized with careful thought to where you are

going and to tight rope discipline.

We had a snack while getting the gear together for glacier travel. The glaciers on Mount Rainier are full of

crevasses, most of which are covered with snow bridges so you can't tell where they are. All you know is that

under your feet might be a giant hole hundreds of feet deep; therefore, it's necessary to rope up. If you break

though the layer of snow covering a crevasse, it is up to the other climbers on the rope to catch you and after

that pull you out of the hole. This can be fairly easy or really hard, depending on lots of different variables.

It's actually pretty scary what can happen, but the risks can be minimized with careful thought to where you are

going and to tight rope discipline.

Dropping down onto the glacier, we started a long, slightly downhill traverse that wound around a few crevasses

while following a boot track from previous parties. Partway across the glacier it started to rain for real. We put

on our Gore-Tex jackets and kept going, hoping to make it to our planned campsite. It seemed to take forever, but

we finally made it to the ridge overlooking the Carbon Glacier. Quickly digging in a tent site, we set up our

camp. It continued to rain all night with strong winds threatening our tent and keeping us awake. By morning the

rain had stopped and the wind had died down. When we got up it was totally clear with the wind blowing a big snow

plume off the summit. It looked very inhospitable up there, and we were glad to still be down here. Later we

learned that this was when the party of four ahead of us started their summit bid from Thumb Rock.

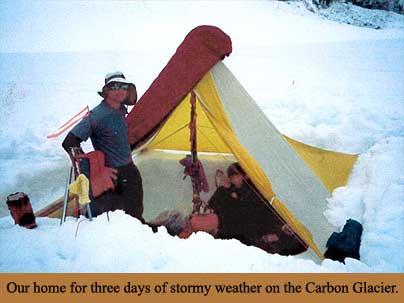

After making some breakfast and drying out our stuff, we decided to descend down onto the glacier itself to try to

get off the exposed ridgeline we were on. Once down on the glacier, we picked a new site and started to dig in our

tent. The tent we were using is a pyramid style using a single pole in the center with no floor. The idea is to

dig a square hole in the snow to pitch the tent over. We spent an hour doing this while the clouds came in again.

Just as we had the tent set up the rain started. We got in our tent and that was where we stayed all day. It

rained for 18 hours straight, never letting up; the wind gradually picked up during the day and by evening was

blowing pretty hard. Just as it got dark, disaster struck. Our tent pole, which was already jury-rigged to make it

longer, broke in a big gust of wind! It was pouring rain and the wind was howling and suddenly we were in

jeopardy. Quickly we started figuring out how to fix the pole. Using the handle of the snow shovel and lots of

webbing we strapped the tent pole back together. After an hour of tense work we had the tent back to normal.

The wind blew all night, but by Wednesday morning it was starting to calm down. Emerging from our tent we were

greeted with clearing skies. Around 9:00 a.m. we called the ranger station on the cell phone for a weather

forecast. Ranger Dave gave us the good news that the weather was going to continue to improve for the next several

days. Then he asked us if we had seen a group of four climbers on our route. We told him no, we had seen no one

since Monday. Shortly after the phone call we heard the helicopter. At first I didn't connect it with the four

climbers Ranger Dave had asked about. Jenny immediately assumed correctly that it was a search helicopter looking

for someone above us on the mountain. What we didn't know was that there had been a tragedy above us.

The wind blew all night, but by Wednesday morning it was starting to calm down. Emerging from our tent we were

greeted with clearing skies. Around 9:00 a.m. we called the ranger station on the cell phone for a weather

forecast. Ranger Dave gave us the good news that the weather was going to continue to improve for the next several

days. Then he asked us if we had seen a group of four climbers on our route. We told him no, we had seen no one

since Monday. Shortly after the phone call we heard the helicopter. At first I didn't connect it with the four

climbers Ranger Dave had asked about. Jenny immediately assumed correctly that it was a search helicopter looking

for someone above us on the mountain. What we didn't know was that there had been a tragedy above us.

Based on the weather forecast we decided to begin the climb the next day. Since we were going to spend one more

day on the glacier, we dug a new hole and moved the tent. We spent the rest of the day drying out our gear and

preparing to leave early in the morning. Chris had brought along a portable CD player and we all spent some time

listening to music and just generally relaxing.

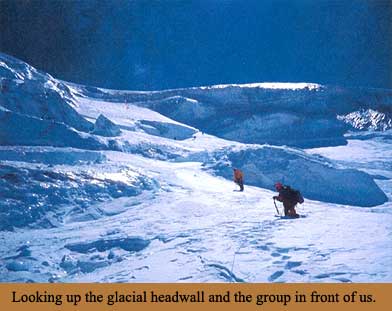

We got up at 5:30 the next morning to clear skies. By 8:00 a.m. we were all packed up and ready to go. We hiked

about three hours up the ever-steepening glacier. We passed beautiful star-shaped crevasses, sometimes crossing

them over snow bridges, and finally reached the base of Liberty Ridge. We climbed up some steep snow then onto a

muddy slope. Rock bands loomed overhead as we traversed around the corner and onto the right side of the ridge.

Now we were really climbing! Up 50° snow/ice slopes, occasionally placing snow pickets for fall protection. Short

scrambles up and over rock bands. Always with an eye out for rocks that would fall from the cliff bands that make

up the ridgeline. Speeding down the slope, eventually rolling all the way to the glacier thousands of feet below.

After several hours of climbing, we gained the ridgeline again at the base of the Thumb. Another 100 feet to the

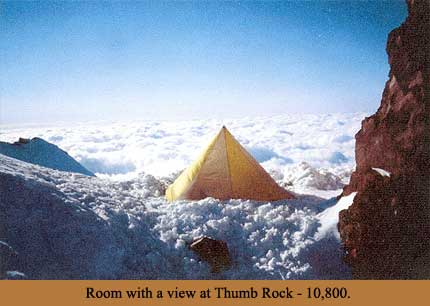

tiny saddle formed by the Thumb. The Thumb is a prominent gendarme at 10,800 feet. This is the normal campsite

used by most climbers doing this route.

The saddle is a pretty small place with room for only a couple of tents. For now we had the place to ourselves, so

we started digging out a tent platform in the main spot. It took a couple of hours of shoveling snow and chopping

ice with our axes to make a nice tent site. As we were finishing the excavation, four more climbers arrived. These

guys were from Colorado and like us, had been hoping the weather would clear. Alex, the leader of their party, had

been on Liberty Ridge two times before, both times forced by bad weather to retreat off the ridge. He was pretty

determined to make it this time, though. They also brought the bad news that there had been a death on the

mountain. According to what they had heard, a party on Liberty Ridge had run into problems after summiting in the

storm two days ago. The details were sketchy, but they were pretty sure someone had died. This was pretty sobering

news and confirmed what we thought might have been happening with the helicopter the day before. What we hadn't

thought about was the fact that the victims had been climbing the same route we were on and that we had been

following the tracks of the doomed party all day. Somehow though we felt removed from the tragedy; we never even

thought about turning back.

The saddle is a pretty small place with room for only a couple of tents. For now we had the place to ourselves, so

we started digging out a tent platform in the main spot. It took a couple of hours of shoveling snow and chopping

ice with our axes to make a nice tent site. As we were finishing the excavation, four more climbers arrived. These

guys were from Colorado and like us, had been hoping the weather would clear. Alex, the leader of their party, had

been on Liberty Ridge two times before, both times forced by bad weather to retreat off the ridge. He was pretty

determined to make it this time, though. They also brought the bad news that there had been a death on the

mountain. According to what they had heard, a party on Liberty Ridge had run into problems after summiting in the

storm two days ago. The details were sketchy, but they were pretty sure someone had died. This was pretty sobering

news and confirmed what we thought might have been happening with the helicopter the day before. What we hadn't

thought about was the fact that the victims had been climbing the same route we were on and that we had been

following the tracks of the doomed party all day. Somehow though we felt removed from the tragedy; we never even

thought about turning back.

At 3:30 a.m. the alarm is beeping and getting out of the sleeping bags is hard. Firing up the stove, we start the

morning ritual of making water and food, packing everything up and putting on our boots. It was 6:00 a.m. before

we were ready to go. The other guys had started about 20 minutes before us, leaving a nice set of boot tracks for

us to follow.

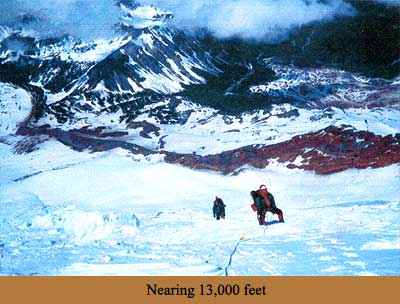

We started out going up and left of the ridgeline on a steep snow slope of about 50°. We were roped together about

40 feet apart. I was in front, Jennifer was in the middle of the rope and Chris was on the bottom. With every

other step or so, we would plant our ice axes in the snow. The axes were attached to our harnesses with a loose

sling; this way, if you slipped while stepping up hopefully your axe would prevent a fall. Every now and then when

it got extra steep I would place a snow picket and clip the rope into it. This way, if someone fell and was unable

to self-arrest the anchor would hopefully stop a slide down the mountain. As we wound our way up the ridge, the

snow would turn to ice in places and here I would place ice screws in the ice for protection. When we got to the

first real ice section, we caught up with the other party who were going slowly in the icy sections. We used this

opportunity to take a break, drink some water and sort the gear. Continuing up, there were times when we would

have to cross back and forth from one side of the sharp ridgeline to the other, sometimes actually going down

around rock outcroppings, always with big exposure below us keeping us all too aware of the consequences of a big

fall. At times the wind would blow pretty hard with the gusts threatening to knock us off our feet. When this

happened we had to just stop and hang on until the wind let up. Six hours of this brought us to 12,500' where the

glacier that flows off the summit begins. Here we switched to leading mode, where I would climb a full rope length

while being belayed, placing ice screws for protection. When the rope ran out I would set up anchors and then

belay Chris and Jenny up. This was a much slower way to go, but it was glare ice with near vertical sections.

Three pitches later we were back on the snow and able to climb together again.

We started out going up and left of the ridgeline on a steep snow slope of about 50°. We were roped together about

40 feet apart. I was in front, Jennifer was in the middle of the rope and Chris was on the bottom. With every

other step or so, we would plant our ice axes in the snow. The axes were attached to our harnesses with a loose

sling; this way, if you slipped while stepping up hopefully your axe would prevent a fall. Every now and then when

it got extra steep I would place a snow picket and clip the rope into it. This way, if someone fell and was unable

to self-arrest the anchor would hopefully stop a slide down the mountain. As we wound our way up the ridge, the

snow would turn to ice in places and here I would place ice screws in the ice for protection. When we got to the

first real ice section, we caught up with the other party who were going slowly in the icy sections. We used this

opportunity to take a break, drink some water and sort the gear. Continuing up, there were times when we would

have to cross back and forth from one side of the sharp ridgeline to the other, sometimes actually going down

around rock outcroppings, always with big exposure below us keeping us all too aware of the consequences of a big

fall. At times the wind would blow pretty hard with the gusts threatening to knock us off our feet. When this

happened we had to just stop and hang on until the wind let up. Six hours of this brought us to 12,500' where the

glacier that flows off the summit begins. Here we switched to leading mode, where I would climb a full rope length

while being belayed, placing ice screws for protection. When the rope ran out I would set up anchors and then

belay Chris and Jenny up. This was a much slower way to go, but it was glare ice with near vertical sections.

Three pitches later we were back on the snow and able to climb together again.

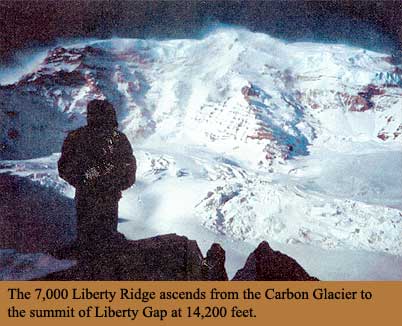

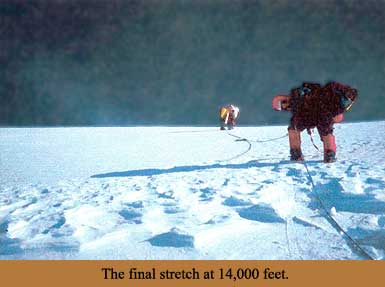

By now we could see the headwall below the summit, a big cliff band of ice stretching across the mountain. We

could see the four guys above us trying to traverse out right onto the upper face, but I thought it looked easier

to climb straight up the shortest part of the cliff to the left. By the time we got up to the base of the wall,

the other guys were returning back to where I was getting ready to lead the headwall pitch. I started up placing

screws for protection. The first 10 feet or so was dead vertical, then the angle eased off a little and I climbed

up and left on solid glacier ice for about 60 feet until reaching a snow-filled crevasse that arched back to the

right. I followed that until the rope ran out. Here I set up a belay with some of the other party's ice screws,

which they had given us to use in exchange for giving them a belay up the headwall. Jenny followed, then Chris who

trailed the other parties' rope. One more pitch along the crevasse took us to the base of the final snowfield.

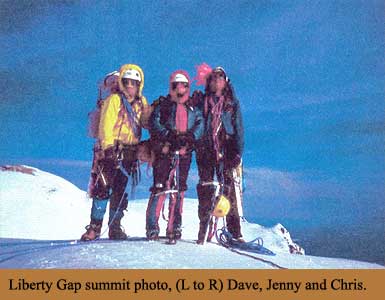

Switching back to simul-climbing, we started up the final few hundred feet. Cresting the upper ridge we marveled

at the views, and then at last we were on the summit of Liberty Cap.

Wow, we had done it, all the doubts and fears erased. Jenny had brought along a bead from Nepal that Pete Whitaker

had given her 13 years before when she originally climbed Mount Rainier. We were all a little bit choked up when

she threw it off the top. By this time it was about 7:00 a.m. and we were all pretty dehydrated and hungry, so

after a few pictures we set off down the mountain. The adventure was far from over though, as we had to descend

5,000 feet down the crevasse-filled Emmons Glacier to Camp Sherman. We were pretty tired by now, so we were going

slowly and carefully. Eventually, the other party caught and passed us, but they were in even worse shape than us.

Alex, their leader who had broken the boot trail all day, was the only one of their team that was unfazed. All the

other guys were staggering down the mountain with frequent rest stops. Soon the headlamps came out as we continued

down the seemingly endless descent. Finally at 11:30 p.m. we got to Camp Sherman. It had taken us seventeen and a

half hours and we were exhausted.

Wow, we had done it, all the doubts and fears erased. Jenny had brought along a bead from Nepal that Pete Whitaker

had given her 13 years before when she originally climbed Mount Rainier. We were all a little bit choked up when

she threw it off the top. By this time it was about 7:00 a.m. and we were all pretty dehydrated and hungry, so

after a few pictures we set off down the mountain. The adventure was far from over though, as we had to descend

5,000 feet down the crevasse-filled Emmons Glacier to Camp Sherman. We were pretty tired by now, so we were going

slowly and carefully. Eventually, the other party caught and passed us, but they were in even worse shape than us.

Alex, their leader who had broken the boot trail all day, was the only one of their team that was unfazed. All the

other guys were staggering down the mountain with frequent rest stops. Soon the headlamps came out as we continued

down the seemingly endless descent. Finally at 11:30 p.m. we got to Camp Sherman. It had taken us seventeen and a

half hours and we were exhausted.

Quickly we set up the tent and started the stove to melt snow since we hadn't had any water for five hours. Jenny

was too tired to wait and just crawled into her sleeping bag barely taking off her boots. While I was unpacking my

stuff, my sleeping bag slid away from me on the icy surface of the snow. I heard a slithering sound and turned in

time to see my sleeping bag speeding away down the slope. I started to run after it but it was no use-my bag was

gone! I had to face a night without it; luckily it was not very cold that night, so I was OK wearing two down

jackets in a bivi sack.

The next morning (Saturday) we awoke to the sounds of several parties setting off up the Emmons Glacier on their

own summit quest. As we ate the last of our food and tried to rehydrate, we heard the whole story of the tragedy

from some of the people that had come up the day before. Three people out of a team of two couples had died two

days ago near the top of Liberty Cap during the worst of the storms. Apparently they had been lost in the storm

while trying to find the way down and had ended up near the edge of the ice cliff at the top of the Whinthrop

Glacier. While trying to dig a snow cave, one of the guys had fallen over the edge several hundred feet down the

cliff. The second guy had put the girls into the collapsing snow cave and then tried to go down to help his

partner. He also fell, tumbling down hundreds of feet, knocking himself out. When he woke up he was missing one of

his boots and was pretty battered. Unable to climb back up to the girls, he started down, hoping to get help.

Eventually, he met some other people and used their cell phone to call for help. But by then it was too late for

the girls. One of them had tried to go down to where her boyfriend's body was and had fallen to her death. The

other girl had frozen to death by the time a rescue was organized. Accidental death always seems so unnecessary

and avoidable, but things happen, and the rest of us seem somewhat callus to just carry on. But it's sort of like

knowing that people die in car accidents, yet we all still drive every day taking our chances anyway.

Soberly, we packed up for the last time and started down the mountain. On the way down we heard more bad news from

people coming up. There had also been a bad accident on Mount Hood in Oregon where several people were killed. To

make matters worse, there was a gnarly helicopter crash during the rescue effort that was being filmed when it

happened. This along with the Mount Rainier accident was being shown on national news. It was then that we started

thinking that our friends and family might be worried that we were the victims on Rainier. We could just imagine

headlines saying " Three People Die on Liberty Ridge" right during the same time we were supposed to be on the

route. As it turned out, that was pretty much what happened. Everyone thought it might be us at first, but

eventually there was enough information out to dispel their fears. When I finally checked the messages on my cell

phone, there were at least a dozen calls wondering where we were.

Soberly, we packed up for the last time and started down the mountain. On the way down we heard more bad news from

people coming up. There had also been a bad accident on Mount Hood in Oregon where several people were killed. To

make matters worse, there was a gnarly helicopter crash during the rescue effort that was being filmed when it

happened. This along with the Mount Rainier accident was being shown on national news. It was then that we started

thinking that our friends and family might be worried that we were the victims on Rainier. We could just imagine

headlines saying " Three People Die on Liberty Ridge" right during the same time we were supposed to be on the

route. As it turned out, that was pretty much what happened. Everyone thought it might be us at first, but

eventually there was enough information out to dispel their fears. When I finally checked the messages on my cell

phone, there were at least a dozen calls wondering where we were.

As we walked the last few miles down the mountain, we reflected on the striking difference between our climb and

the tragic one. So close together, yet so different. We had a basically perfect climb, but the potential for

mistakes and tragedy always lurks just one or more bad decisions away. In the end it's never too hard to justify

the risks of doing the things we love to do, whatever that may be. There's an old saying, "Its better to have

loved and lost than to never have loved at all." How about, "It's better to have lived and then died than to never

have lived at all"?

Dave Wonderly 2003

(Editors note: Dave Wonderly is a founding member of the RADS and Warrior's Society mountain bike clubs.)

|