Contents

Opening page

Editorial Staff

Introduction

Club and General News

Warrior's Racing

Access Updates

Featured Stories:

Triumph and Tragedy on

Liberty Ridge

Why I Love Mountain Biking

Between Spring Rains

The Biscuit Fire

All in a Day's Ride

Guest Commentary

Nature vs. Politics:

Greenpeace is Wrong

to Oppose Logging.

Commentary

The Price of Freedom

Closing Thoughts

|

Featured Stories continued

The Biscuit Fire: Access and the Green Lie

By Don Amador

Often billed as the worst wildfire in Oregon's history, the 2002 Biscuit Fire destroyed more than 460,000 acres of

forestland in the Siskiyou National Forest. Started by lightning storms last summer, it also devastated

approximately 28,000 acres in the Six Rivers National Forest located in northwest California.

On May 22, 2003, I toured the Biscuit Fire in the Smith River National Recreation Area. Scott Sinclair, a former

U.S. Forest Service recreation specialist on this unit, also joined the review. Both of us were shocked by the

visual impact of this biblical-scale event. Looking north into Oregon and westward to the coast, brown mountains

covered with trees looking more like black matchsticks was all that remained of once majestic timber stands of

Port Orford cedar, Jeffery pine, and Douglas-fir.

On May 22, 2003, I toured the Biscuit Fire in the Smith River National Recreation Area. Scott Sinclair, a former

U.S. Forest Service recreation specialist on this unit, also joined the review. Both of us were shocked by the

visual impact of this biblical-scale event. Looking north into Oregon and westward to the coast, brown mountains

covered with trees looking more like black matchsticks was all that remained of once majestic timber stands of

Port Orford cedar, Jeffery pine, and Douglas-fir.

From my perch on an overlook, I was also impressed by the fact that a heroic campaign was waged last year by the

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, equipment operators from the Simpson Timber Company, and

Forest Service firefighters to save the town of Gasquet, California.

Several access roads and the Elk Camp Ridge Trail appeared to have played a critical role in the battle to protect

residents and resources. It was clear that backfires from these forest travel ways were used to successfully halt

the southern march of the Biscuit Fire. The trails also provided access for crews to cut fire lines, provide

supply routes, and clear forest fuels.

Either due to a lack of roads or prohibitions on mechanical management, or both, the fire was apparently allowed

to burn through the Kalmiopsis Wilderness and certain roadless areas until they could be successfully engaged by

ground forces using access roads and trails in other regions of the Siskiyou and Six Rivers National Forests.

As I gazed westward from Elk Camp Ridge Trail to the now lunar-like landscape of the High Plateau or North Fork

Smith River Special Interest Area (SIA), I couldn't help but remember the political battle recreationists waged

several years ago to keep anti-access groups from closing forest roads in the SIA to motorized use. The irony of

that road closure and subsequent decision to leave the land alone is that they were enacted to supposedly "protect

exceptional botanical and ecological values."

On January 23, 2001, the BlueRibbon Coalition, a national recreation group, asked the Six Rivers National Forest

to reconsider its efforts to close access roads in the SIA. The Coalition suggested that the Forest Service adopt

our "managed access alternative," a balanced proposal, because we felt the two closure alternatives and the no

action alternative were "not acceptable to the backcountry/dispersed recreation public."

On January 23, 2001, the BlueRibbon Coalition, a national recreation group, asked the Six Rivers National Forest

to reconsider its efforts to close access roads in the SIA. The Coalition suggested that the Forest Service adopt

our "managed access alternative," a balanced proposal, because we felt the two closure alternatives and the no

action alternative were "not acceptable to the backcountry/dispersed recreation public."

The recreation community had offered to support only permitted access or seasonal closures. We even advocated a

wash station to help prevent the spread of Port Orford cedar root disease, a concept now validated by the 2003

Biscuit Fire Burned Area Emergency Rehabilitation assessment.

Sadly, the agency decided on its plan to close almost 25 miles of recreation roads to the general public with

support from the California Native Plant Society, the Sierra Club, and the North Coast Environmental Center. The

closure came even after we told them that cedars in the High Plateau area had never been infected in over 30 years

of motorized access.

As I now look at the charred skeleton of the "Sentry Tree," a venerable 100-foot Port Orford cedar that once stood

watch at Diamond Creek dispersed campground, the big lie of "preservation" struck me.

The public has been sold a bill of goods by extreme green groups when they say that "preservation" or

non-management of, or no access to, our public lands is good for the environment. The "protected and preserved"

status of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness area in Oregon and the High Plateau SIA in California were completely ignored

by the destructive forces of nature.

The Biscuit Fire also may have proved that access closures to the public are statistically insignificant when

compared to the impacts of natural catastrophes. In fact, those closures appear to have impeded the firefighter's

initial efforts to attack the blaze.

This wildfire has exposed the eco-myth that banning public access will protect the environment. Today anti-access

eco-groups want to once again "protect" these areas as they fight administration efforts to improve forest health

and, as always, Mother Nature will expose the folly of their approach.

Don Amador writes on environmental and access issues from Oakley, CA. He is a consultant to the

BlueRibbon Coalition.

|

All in a Day's Ride

By Ken James

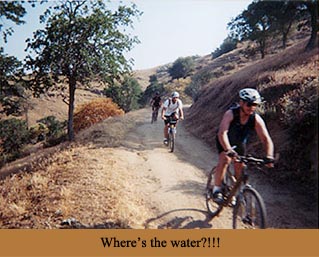

The date was June 8, 2003. The time was 6:15 a.m. It started out to be a nice day. The weather was a mild 75-80

degrees. Our planned ride was to consist of making a loop up Cow Flat, up Brickenridge, and then down Remington

Trail. Some of us the day earlier placed water and food in places for us to refill our water and food needs. We

knew that it was going to be a hot day for the ride ahead. Anyway, the ride up Cow Flat was comfortable. It was

nice to talk with new riders and catch up with our buddies. We finally made it to the top of Cow Flat. The long

pull of Brickenridge was here. About a mile we filled up with water. The temperature was now about 93 degrees and

we knew we had to keep hydrated or the dreaded cramps could come upon us. The pack was starting to separate and

good ol' Leon told us to go ahead and he would stay behind with the back of the pack. My group of about five

riders was looking for the next water station. They kept looking at me and asking, "Where did you put the next

water?" I had never ridden this before, but I was there yesterday and had that puzzled feeling. "Ah, should be

just around the corner," I kept saying. I think they were ready to give me some physical abuse anytime. Finally we

made it.

nice to talk with new riders and catch up with our buddies. We finally made it to the top of Cow Flat. The long

pull of Brickenridge was here. About a mile we filled up with water. The temperature was now about 93 degrees and

we knew we had to keep hydrated or the dreaded cramps could come upon us. The pack was starting to separate and

good ol' Leon told us to go ahead and he would stay behind with the back of the pack. My group of about five

riders was looking for the next water station. They kept looking at me and asking, "Where did you put the next

water?" I had never ridden this before, but I was there yesterday and had that puzzled feeling. "Ah, should be

just around the corner," I kept saying. I think they were ready to give me some physical abuse anytime. Finally we

made it.

Back to the long pull up Brickenridge. At the top we weren't sure which way to turn. We picked the right turn but

found out that a rider went the wrong way and added 4 miles. The top was here! we thought!! We were told that once

at the top it was a nice 4-mile downhill to the vehicles. WRONG! Turned out to be the worst hills of the ride. It

wasn't a ride at this time. It was a nice "hike-a-bike." Not only was this some tough trail, this trail wasn't

marked very well and many questioned if we were going the right way. "They said it was downhill and we're going

uphill." :( While we sat there questioning which way to go, the flies had their way with us! They drove me fricken

nutts! Earl and I decided that there were some tracks of bikes in front of us, so we took off. I'd take the chance

of going the wrong way instead of letting those *%^%*%*%* flies amputate me! We finally saw the blue skyline and

knew it was close to downhill.

Downhill was technical, but a blast! 9.5 hours later my little powerhorse Nissan pickup was in front of me! I had

1/4 of a CamelBak left. Too close. Some other riders came in about 15 minutes later. They said that they were all

cramping up and out of water. They said they couldn't find the hidden water to refill and were worried about the

back group. There still were eight riders to come in. About 5:30 p.m. I started worrying. I called a fire station

and informed them of the situation. A chief called me and told me that he didn't want to be looking for riders at

night and, like me, was concerned of the lack of water and dehydration problems. Search and Rescue was initiated.

Downhill was technical, but a blast! 9.5 hours later my little powerhorse Nissan pickup was in front of me! I had

1/4 of a CamelBak left. Too close. Some other riders came in about 15 minutes later. They said that they were all

cramping up and out of water. They said they couldn't find the hidden water to refill and were worried about the

back group. There still were eight riders to come in. About 5:30 p.m. I started worrying. I called a fire station

and informed them of the situation. A chief called me and told me that he didn't want to be looking for riders at

night and, like me, was concerned of the lack of water and dehydration problems. Search and Rescue was initiated.

Here we go. Had a Kern County chief's vehicle, a Kern County patrol, a chief with Dept. of Forestry, a crew of

eight with Dept. of Forestry, two sheriff's vehicles, and couldn't finish without a helicopter! What service! I

stayed with the vehicles at the finish along with my emergency personnel friends. Earl hopped in his vehicle,

drove to Bodfish after getting more water for them, drove to Brickenridge, and then drove down Cow Flat just in

case looking for the riders. The helicopter made it over us and spotted the riders. They were about 15-20 minutes

out and looked to be OK. Tim was the first one in of the group. He just shook his head smiling yelling for his

camera. All turned out to be OK. I would call this ride a "test" for many of us. It tested our patience and our

bodies. I learned a lot from this ride. I hope some others did too!! You know what, though? I'd still do it again

instead of sitting in front of the boob tube. Life is good! Thanks guys.

Ken

|

|